- Home

- David L. Major

The Day of the Nefilim Page 2

The Day of the Nefilim Read online

Page 2

They went into the bar and sat around one of the white plastic tables in the beer garden. From here, they had a clear view across the water, where outcrops of volcanic rock dotted the sand dunes like raisins on a cake. From here, the only sign of human activity was the small dark mass of tents, buildings and fences.

It was a hot day. The sun was strong, and despite the shade provided by the umbrellas of the beer garden, the half dozen starched white collars quickly became limp with perspiration. The talk was of politics and careers.

After a while they leaned back in their seats and marveled, each one to himself, at the wonderful and important things that were happening beneath the sand and rock across the water, and how fortunate they were that history had chosen them to do this work.

Except the General, of course; he had chosen himself. He sat silently while his subordinates talked, tapping his fingers lightly against the side of his glass. If there weren’t appearances to keep up, he might even have been smiling to himself.

* * *

A map gives up its secrets

A long way from the garden bar at the Red Lion…

ON THE SHIP, Thead is unconcerned by the fact that they have been unable to continue their voyage, and is equally uncaring about the success of Onethian and Sahrin. He has his own project to think about, and he feels one of life’s important moments approaching. It is the crossing of a threshold – a tide reaching its high-water mark. This has been a long time coming, and the moment belongs more to him than anyone else; it is the unraveling of the secret of the map.

Thead sits back and runs his hands though his thinning shoulder-length hair. His skin, rough and pockmarked, is shiny with sweat from his exertions, even though they have all been cerebral in nature. His eyes, normally thin and constantly shifting, widen momentarily as he makes a connection on the maze before him. He smiles to himself and leans back over the map.

It was given to one of the ship’s former crews, at a place they visited so long ago that its name has long been forgotten. Since then, it has taken on great importance to all the crews of the ship, from those whose names are lost in antiquity down to the six who make up the crew of the present day. A rich mythology has formed around the parchment. The mysterious territory which has its features drawn on the faded surface is part ancestral homeland, part legend.

The map has long been Thead’s obsession. Long after the curiosity of others has turned away and settled down into a collection of comfortable and reassuring myths, he still studies it relentlessly.

He crouches down among the tall, gangling structures of the ship’s foredeck, in a makeshift study created from barrels and boxes and sheets that he has taken from the cargo hold. Here he spends his days, and here he is today, sheltered from the wind and the distraction of his crew mates, bent over his precious parchment.

When he is sure of a new realization, he makes the faintest of marks on the parchment – a circle, a line, an arrow – in soft graphite that can easily be removed, his touch is so deliberate and light.

The maze of symbols and labels are sometimes in a language familiar to him, but most of them are in a foreign script, the slow deciphering of which has been his work. Its flourishes and curlicues never cease their whispering to him; sometimes he hears the voices through the night as he dreams. Sometimes his dreams have form, as though they are populated by entities, and those nights are not easy. It is better when the dreams don’t come.

The rest of the crew is happy enough to leave Thead to his musings. And Bark, of course, is happy with things that way as well. There are members of the crew with whom he has easier relationships.

It makes sense that there should be someone working on the map, and it is as well that it is Thead. Practical tasks have never suited him, and the rest of the crew would be distracted if Thead were to spend too much time with them. There is something about him that makes them uneasy.

The hull of the ship creaks as it floats, moving listlessly in the gentle current.

Apart from Onethian and Sahrin, who are busy with the new rudder, the crew has nothing to do. Bark is still asleep on his pile of sacks. The Senator is working on another one of his speeches that he will never deliver, and Kali is below decks, in the galley.

Thead feels a rush that surges through his whole body. Steadying his hand to keep it from shaking, he makes a faint mark on the map.

The final piece of the key falls into an ancient lock.

He has it! He leaps up and runs the length of the ship, shouting, waving the map above his head. Idiot, Onethian thinks.

At first no one else understands the reason for the disturbance, but they soon recognize what he is holding. They drop what they are doing and follow him, even Onethian. This must be a good day. First the rudder being fixed, and now this...

Thead crouches down beside Bark and spreads the parchment out on the deck. The others gather around and watch intently, without understanding, as Thead guides Bark through the glyphs and symbols.

When Thead finishes speaking, his finger is slowly circling a small and insignificant looking set of marks on the map.

Bark straightens and looks up. He is wide awake now. He stretches as he contemplates the clouds wrapping themselves into cool wreaths around the ends of the ship’s masts. All around them, hills of denser cloud lie stacked one upon the other, reaching as far up and as far down into the depths below them as anyone can see. The more distant clouds move slowly, carried by the most gradual and impartial of tides.

But something apart from the clouds is moving. Bark can feel it. It is their future that is spread out before them on the deck.

But do they complete their mission, and deliver their long overdue cargo, or do they follow the course that Thead has discovered on the map?

All of them feel the answer. It isn’t long before the rudder is in place, and as soon as everything is ready, they set sail.

It exhilarates them to be moving again. The sight of the billowing mountains of cloud in movement lifts their spirits, and even the ship itself seems to rejoice as it carries them along.

They follow Thead’s directions. The seductive joy of submission to a higher purpose spreads through the crew. The wind seems to catch their enthusiasm, and it picks them up, bearing them along confidently. They sail down narrow byways and across vast uncharted wastes of space. They cross darkness and light, places where there are no clouds, and places where there is nothing but cloud. They see strange creatures in even stranger skies, such that no one would believe. They see signs and wonders. The cargo lies forgotten in the hold.

Finally, after a long time, and several adventures that in normal circumstances would themselves be considered sufficiently unusual to warrant retelling, they arrive above a new land.

* * *

A brief history of Barker’s Mill, and Reina makes plans for the weekend.

A CENTURY AGO, THE HILLS ACROSS THE HARBOR from Barker’s Mill had been covered with forest. Giant trees, hundreds of years old, towered over dense confusions of bush. Then a new type of human arrived, different from the ones who had lived there before. The original inhabitants’ small numbers and simple lifestyle had not lain heavily upon the land, unless you counted the extinction of a few species of large flightless birds that were good eating and easy to catch.

These new humans wore heavy clothing to protect themselves against the weather, and they wore boots on their feet. Their horses pulled carts through the mud of the paths that they cut through the forest. They chopped down the trees and cut them up and put the lengths of wood on the carts. They left behind piles of burning branches, and all the rubbish that followed them everywhere. The hills were soon becoming bare.

They took the cut wood around the harbor, to where an individual named Barker had built a timber mill and where houses were appearing in clearings carved out of the forest. Soon there was a town, with a store and a school. The town came to be known as Barker’s Mill.

The people of Barker’s Mill built them

selves a church in which they gathered to celebrate their good fortune.

For the next few decades, the town amassed a degree of wealth by removing the rest of the trees from the hills around the harbor and selling the timber to anyone who would buy it. When the forest was gone, the mill closed down. The sons and daughters of the Barker family, now rich, moved elsewhere.

Where the forest had once been and where there was now none, the hillsides gave way under the rain. The topsoil, now dust, muddied the water as it ran down to the sea, or it was lifted by the wind and carried away, falling to the ground as a fine layer of annoying gray dust that discolored everything. After a few years, the sand and rock that had supported the topsoil were totally exposed.

Once the sand was uncovered, there was nothing to stop it from sliding off the hillsides. Streams became choked and then dried up altogether. Their beds disappeared under the sand. It was said by the locals that somewhere under the sand were buried the remains of an old village in which a few natives and settlers had lived together even as the forest was disappearing. No one knew the identities of the people who had lived there, just as no one knew where they had gone after the sand had flowed over their houses. There were stories, though.

There was another story as well, a much older one, which belonged to the indigenous people. Their legends told of another race that had lived in the area, long ago. But those stories were ancient now, and almost entirely forgotten. A few of the old people remembered fragments of them, and the young didn’t care.

They didn’t care because the legends were from the past, from the old world of spears and weaving flax and cooking food in the ground, and this was now. Most of the young people moved to the city and never came back. The area had its own history now, and the people who lived and worked there were fourth, fifth, and sixth generation. They were the locals now, and anyone who rolled through here in a convoy, army or otherwise, in trucks or shiny cars, was an outsider.

When she got into town, Reina pulled up outside the Red Lion. It was hot and dry, and she had time for a drink before unloading at the buyer’s. Crossing the street, she saw the black cars sitting in the car park. If it weren’t for the two uniformed drivers leaning against the side of one of them, talking and smoking, it would have looked as though the mob was in town. She went in.

Bryce was sitting at the bar.

Reina sat beside him. She dropped a note on the bar and pointed at one of the taps. The woman behind the bar put a beer in front of her. “Thanks, Denise.”

“What do you make of these?” Bryce nodded towards where the officers sat, sweating in the shade.

“Their trucks passed me on the way in. Big ones, covered with tarps. Machinery or something,” Reina replied. “I suppose they’ve gone over to the dunes?”

“Yeah, the trucks and the other stuff shot straight through. This lot must think they’ve earned a break. Pretty, aren’t they? Nice braid, shiny medals...” He was talking deliberately loud. A couple of the officers turned and looked coldly in their direction.

“Jesus, keep it down…” Reina laughed, not really caring whether he did. She was well acquainted with his ideas about the military, authority, and the system in general. He was an anarchist, and he didn’t mind who knew it.

Bryce stared back at the officers, goggle-eyed, daring them.

Reina picked up her beer. “Give it up, shithead. What do you think it’s about?”

“You mean none of the theories we’ve come up with have impressed you? You’re a hard woman to please. Shall we go over and have a look?” He nodded towards the open doors. Through them, the dunes on the other side of the harbor were visible.

“Yeah, we haven’t been over for a while, have we. Not now, though. I’m working, as we speak. What about this weekend? After netball?”

“After netball it is, then. A bit of fascist-watching to round the afternoon off. We’ll take lunch and a bottle.”

The officers were about to go when their trucks came into view across the water. From where they sat, the vehicles looked like tiny matchbox toys as they entered the compound, but the comparison never occurred to them. Such thoughts do not commonly exercise themselves in minds such as these. The officers finished their drinks and watched as the compound’s gates closed behind the last of the trucks. Then they got back into their black cars and set off along the road around the bay, leaving clouds of dust hanging in the air behind them.

In the leading car, the General, permanently assigned by his government and his uncle (in this case, the same thing) to the standing army of the United Nations, turned up the air conditioning and loosened his tie. The gin had made him sleepy.

His lethargy was due to more than just the drink, though. He had been feeling haunted all day. The previous night, while he slept, he had dreamed.

There was a huge room… It had walls of dark, finely carved stone and a high ceiling lost somewhere in a darkness that seemed to gather around him like a cold, shifting fog. In the dim light he saw obelisks, twice as high as a man. There was no one in the room, but it lacked the stillness that it should have had. There was a sense of being, of something, which slowly coalesced, taking on a form that was invisible but palpable, that brushed against him like seaweed swirling in a tide. The sensation of voices, a hot, dry rustle of moth wings, fluttered around his head…

When he woke, he couldn’t remember anything of what the voices had said. That had frustrated him at the time, and the memory of it frustrated him now. There was an urgency, he could recall that much. He felt, in his dream and afterwards in the shower, and as he put on his uniform, that they – whatever they were – were trying to tell him something. There was something in the whispered dialogues that made him feel uncomfortable.

In the end he gave up, as practical men should do when confronted with dreams. He had a lot to do.

The General was the only person here who knew everything about the operation. Everyone else, including the archaeologists, knew enough to do their job, and no more. The bigger picture was not their concern.

Of course, there had to be some people whose jobs demanded that they know more than they could be trusted with. It was unfortunate. Sometimes it was possible to clean their brains out – there was technology more than equal to the task; but sometimes memory removal wasn’t possible or appropriate. Sometimes it was necessary that someone disappear. But the General was a reasonable man, and he tried to keep those losses to a minimum.

They were approaching the gates of his new command.

* * *

An arrival

“THIS IS THE PLACE,” says Thead, checking the map, then looking through his sextant, and then through his telescope again, checking and rechecking.

Thead is used to the idea that he is doing an important thing. This place was promised to them a long time ago. They might not know exactly what awaits them, but over successive generations, the ship’s crews have made up stories among themselves. It is those stories that have kept their faith alive through the centuries, and it is those same stories that stir their blood now.

In the direction of the sun, an ocean reaches out towards the horizon. Below them, a coastline meanders slowly away in both directions, indented by bays and inlets. A town, sheltered by the surrounding hills, hugs the edge of one the larger bays. In its streets they can see life, tiny, like fleas crawling through the fur on a dog’s back.

“Thead,” says Bark after they’ve spent a few minutes looking in silence, “where are we? What does the map say? Where should we look now?” He wants to ask what they should look for, but no one knows, and they all know that no one knows, so there is no point in asking.

Thead is happy now that his opinion matters. “I can’t be sure. We’re in the right area, according to the map. More, I can’t say. There is nothing more on the map that can help us. Nothing that I can see, anyway.”

“We’ll moor the ship there,” says Bark, pointing to the opposite side of the harbor. “Away from the town, above those

dunes.”

They cross the harbor. Bark is enjoying himself. This is a great moment in history, even if it is just the history of the ship, not Big History. It’s as close to a Great Moment as any of them have ever been, with the possible exception of Bark himself, who can recall from somewhere the investiture of some kind of emperor, sometime in something called the Middle Kingdom. Something like that. It was a long time ago, in one of his other pasts.

Near the dunes, Onethian, always first in line to do any physical work, flexes his muscles and leans into the winding gear, letting the anchor descend to the ground. It lodges in the branches of a tree, and the Senator and Sahrin join Onethian as they begin winding the chain in.

The ship descends towards the ground. The three of them strain at their task, and it isn’t long before their skins shine with sweat. “Get lost, old man,” grunts Onethian. “You’re getting in the way.”

“Leave him alone,” says Sahrin as the Senator puffs obediently away and sits down.

Kali, drawn from below deck by the sound of the winch, goes to one of the viewports and immediately calls out.

Below them, sitting on a ledge of rock among the sand dunes, are three people.

The ship, along with themselves, is invisible to the local inhabitants, so they aren’t concerned about being noticed by the three on the ground, but there is still an element of surprise in seeing some of the locals so soon. And for them to be, from this distance at least, the same as the crew; that is to say, human, or at least the same basic shape – that in itself is unusual.

Now they need to make another decision.

* * *

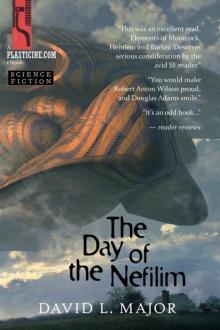

The Day of the Nefilim

The Day of the Nefilim